FBI was warned about Florida school shooting suspect 5 months ago

The stranger’s message on YouTube couldn’t have been clearer.

“Im going to be a professional school shooter,” a person identifying himself as Nikolas Cruz wrote in a comment beneath another user’s video in September.

Corrección:

12:00 a.m. feb. 17, 2018An earlier version of this article said YouTube user Ben Bennight lives in Alabama. He lives in Mississippi.

The declaration was so alarming — so disturbing — that the video’s poster, Ben Bennight, who lives in Mississippi, did what Americans are supposed to do. He called the Federal Bureau of Investigation to warn them.

But following a brief investigation, officials later said, the FBI closed the case, after apparently failing to identify the person who’d made the comment. It would prove to be a missed opportunity of heartbreaking proportions.

On Wednesday afternoon, a South Florida 19-year-old named Nikolas Cruz walked into a high school where he had been expelled for disciplinary problems. He then opened fire with an AR-15 rifle and killed 17 people, officials said.

Cruz escaped, officials said, by trying to blend in with fleeing crowds of students. He stopped at a Subway and McDonald’s and ordered a drink. Not long after, a Coral Springs police officer spotted him walking down a sidewalk, alone. He was wearing the same maroon shirt and black pants the high school gunman had been seen wearing. Within moments, Cruz was arrested without resisting.

The reality was that Cruz was not somebody who blended in. He tormented his neighbors. He posed with guns on Instagram. He was so troublesome at school that he got kicked out, and when he returned Wednesday, a school monitor recognized him and radioed a warning.

Now, yet another grieving community — and a nation roiled by yet another emotional debate over how to prevent mass shootings — must reckon with how a young man who had become a dark joke among fellow students had been intercepted only after an act of mass murder.

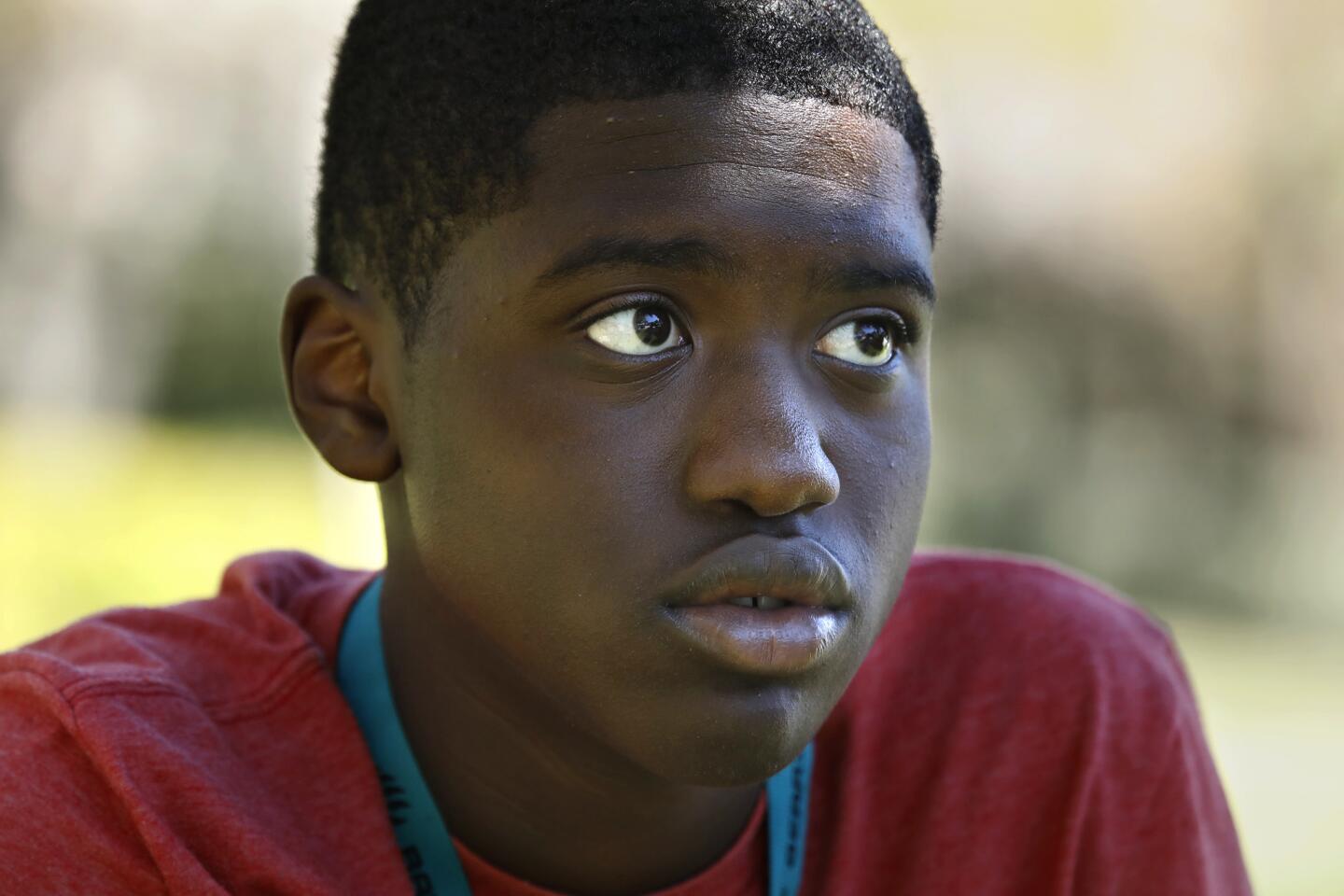

“Everyone called him ‘the school shooter,’ ” said Rachelle Jean, 16, an 11th grader at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, where the shooting occurred. “It was like, he was off.”

Cruz, an adoptee, grew up in the affluent community of Parkland and lived on a peaceful street of upscale homes with lush, manicured lawns shaded by coconut and palm trees.

Pale and slight, Cruz caused alarm among neighbors not long after he moved in. A neighbor complained that he bit their young son’s ear, said Shelby Speno, a 48-year-old videographer who lives two doors down from the family’s former home.

When Cruz was a little older, a neighbor accused him of stealing a check from a mailbox. In middle school, she said, he threw eggs at her husband’s car.

Other neighbors complained that Cruz killed squirrels, poked sticks down rabbit holes and picked fights with other children.

One day, Speno said, she provided a statement to police after her daughter spotted him shooting their backyard neighbors’ chickens with a BB gun.

Up and down the street, neighbors said the police were called to the Cruz home dozens of times.

“I think she had her hands full, I really do,” Speno said of Cruz’s mother, Lynda. “She was always very apologetic.”

Three doors down from the Cruz household, Malcolm Roxburgh, 82, a retired agent for Carnival Cruises, said Cruz would take his dog across the street to attack their neighbors’ pot-bellied pigs.

“He was bad news,” he said. “We all knew he was bad news.”

About five years ago, Roxburgh’s daughter, Rhonda, 45, confronted Cruz after he banged his rucksack into her car’s rear passenger door as she stopped at the end of the street near the school bus stop. He struggled to look her in the eye and looked down as they spoke, but she did not feel reassured when their eyes met.

“That child had an extremely cold stare,” she said. “It was like talking to a brick wall.... There was nothing there. There was just no feeling.”

Gradually, over time, Roxburgh noticed Cruz would just sit on the curb by himself as he waited for the school bus, far away from the other neighborhood kids.

“You could start to see he was isolated,” she said. “Nobody wanted to be around him.”

Roxburgh, who now lives in North Carolina, was so concerned about Cruz she urged her parents to sell their home and leave the neighborhood.

“I knew something was going to happen,” she said. “That young man was extremely challenged. He was just constantly looking for trouble. You could feel he was going to hurt someone.”

When the Cruz family finally moved out, selling their five-bedroom, three-bathroom home in January 2017 for $575,000, many neighbors were relieved.

“Thank heavens!” Malcolm Roxburgh said. “We were all so happy.”

“I hated to say, ‘I’m glad they’re gone,’ ” Speno said. “I tried to be friendly. You know, you try to wave, but he would just stare at you. He was just a little bit creepy.”

After Lynda Cruz died on Nov. 1, Nikolas and his brother stayed with family friends in Lake Worth in Palm Beach County.

Unhappy at that home, Cruz asked a former classmate if he could move in with him and his family. He had been living with them in northwest Broward County, about three miles from the school, since Thanksgiving.

“He was a little depressed because his mother had just died, but he seemed to be coming out of it and doing better,” said Jim Lewis, an attorney representing the family.

Cruz had gotten a job working at a Dollar Tree store, and he was going to school at an adult education center to get his GED, Lewis said.

It seemed like a tentative turn toward responsibility for a student who had been kicked out of school. Hunter Vukelich, 24, a former assistant manager at the Dollar Tree store, said Cruz was reliable, always showing up for shifts, yet timid and introverted: “A little off.”

“You could tell he had something going on in his personal life,” Vukelich said. “But he wasn’t threatening at all.”

Brian Oakes, 40, who owns a dance studio near the Dollar Tree and often pops in to pick up energy drinks and water, said Cruz seemed somewhat normal. “He would seem to mumble stuff under his breath,” Oakes said. “The first time I met him I wondered if he had Tourette’s.”

Online, Cruz seemed to embrace a much darker life. Nine months ago, a YouTube user with the handle “nikolas cruz” posted a comment on a Discovery UK documentary about the gunman in the 1966 University of Texas shooting that read, “I am going to what he did.”

An Instagram account under Cruz’s name showed him posing with guns and in masks. In one post, Cruz wrote anti-Muslim slurs and apparently mocked the Arabic phrase “Allahu akbar,” which means God is great.

Other students who knew Cruz were worried about his gun fixation. “He was posing with toy guns, posing with real guns” in his posts, said Rachelle Jean. “He had an arsenal in his room.”

Investigators said Cruz legally bought the AR-15 semiautomatic rifle used in the attack nearly a year ago in Florida after he turned 18.

He apparently brought the weapon with him when, officials said, he took an Uber to his former school. Armed with smoke grenades and a gas mask, they said, he opened fire shortly before classes were supposed to let out for the day.

Once he slipped away on foot, he bought a drink at a Subway, and then hid for a while at a McDonald’s, authorities said. He was captured 40 minutes after leaving the fast-food restaurant and taken to a hospital after showing “labored breathing.”

When he appeared in court via video for his initial court appearance Thursday, he was wearing an orange jail jumpsuit, looking stooped.

Cruz’s court-appointed attorney, Melissa McNeil, said he appeared to be “fully aware of what is going on.” But she said he had a troubled background, and little personal support before the attack.

He appeared to be regretful about what he seemed to have set out to do months ago — become a school shooter. He’s “sad, mournful, remorseful,” McNeil said. “He’s just a broken human being.”

Suscríbase al Kiosco Digital

Encuentre noticias sobre su comunidad, entretenimiento, eventos locales y todo lo que desea saber del mundo del deporte y de sus equipos preferidos.

Ocasionalmente, puede recibir contenido promocional del Los Angeles Times en Español.