Consumer confidence grows in Brazil as Bolsonaro sparks recovery hopes

For the first time in many years, senior citizen Maria Helena gave in to her love for shopping and filled a cart with dozens of garments from a shop in Sao Paulo, reflecting a new-found confidence in the country’s economy under President Jair Bolsonaro .

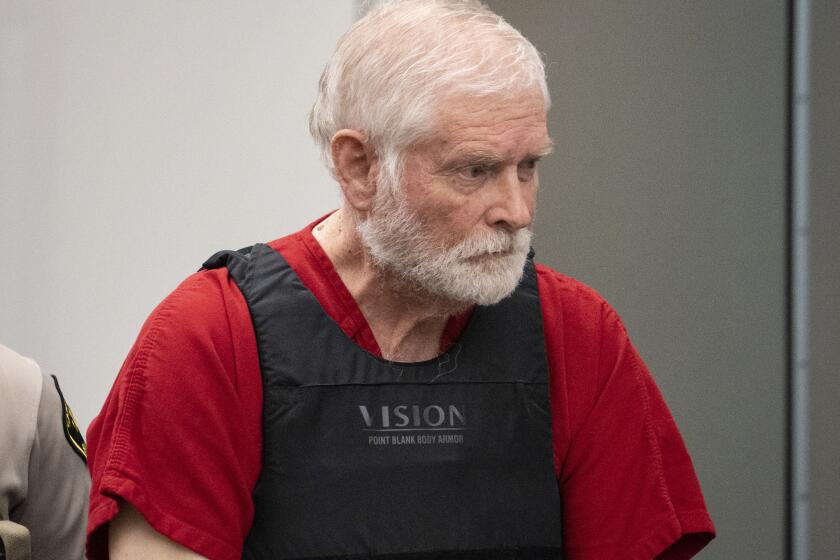

Bolsonaro, 63, the rightwing former army captain, assumed office Jan. 1 after winning polls last year on the promise of big ticket economic reforms and open market policy.

Economic indicators show that consumer confidence at the end of 2018 touched 93.8 points, the highest in five years, following two difficult years of recession in 2015 and 2016 and two years of modest growth.

“Three years ago, I really felt the crisis because there were a lot of people afflicted and I used to see my friends and family in bad condition. But now, we feel a slight improvement,” Helena told EFE.

Consumer confidence grows in Brazil as Bolsonaro sparks recovery hopes Experts claim that the worst maybe over, and believe that the ultra-right president’s proposed neoliberal policy will steer Brazil on the right track, bringing foreign capital into the country, and consequently improving the business environment.

“With improvement in business environment for companies, the people’s confidence to consume also tends to improve,” said Getulio Vargas Foundation economist Virene Matesco.

However, despite improved economic projections for the year, the International Monetary Fund has predicted a growth rate of just 2.5 percent.

Matesco said initially Brazil’s recovery will focus a lot more in reactivating the economy than in generating employment, which will delay the visible signs of improvement.

“There will be contractions, but feeble ones. We will only get a breather and reach reasonable rates of unemployment in 2021, 2022,” he said.

Although the official unemployment rate has fallen to 11.6 percent, which is equal to 12.2 million jobless people, Brazil ended 2018 with a record number of people working in the informal economy.

Although the numbers point towards a small decline in unemployment in recent years, the labor sector continues “to react very slowly and precariously” to the crisis, according to GVF economist Mauro Rochlin.

“We can only talk about a consistent recovery of the economy once we observe a more vigorous labor market,” said Rochlin.

That is why despite great progress in the Sao Paulo stock market, it is still not possible to speak of some kind of “euphoria” in the market, Rochlin said.

In his opinion, investors continue to remain cautious and are waiting to see the measures rolled out by the Bolsonaro government.

“The stock market has now reached 97,000 points, but last year it was being said that it could reach 100,000. So, one cannot say it is a meteoric, explosive rise,” Rochlin said.

Another factor that could weigh in the recovery of the largest Latin American economy is the reaction against forthcoming moves by Vale mining company, which owns the dam that collapsed on Jan. 25, leaving more than 120 dead and some 200 missing.

Since the tragedy, the world’s largest producer and exporter of iron has lost more than 50 billion reals ($13.65 billion) in the stock market.

Even then, Bolsonaro’s promises to roll out reforms and further open the economy appears to have caught on with the business community, including small traders, who believe that the situation will change quickly.

Such is the case of the store manager of Bras Moda, Adriana Katynski, who expects that things will finally start moving and money will resume circulation in 2019.

Katynski said she had already noted signs of recovery in her business, located in a popular shopping district in Sao Paulo.

“Many people were unemployed. They bought only the essential things. Imagine an unemployed family man - between buying clothes and food for his family, which one do you think he would prioritize,” she asked.

Like many in her situation, former nursing assistant Cecilia de Souza said she was suspicious and still hopeful that after all the problems they had gone through, would finally see “the light at the end of the tunnel.”

“I lived through a crisis during the military dictatorship (1964-1985). There was a shortage of milk, meat, rice. I went hungry and I hope this doesn’t happen again,” she hoped.

She said despite the high cost of products, they do not face shortage. “Certainly the people have gone back to shopping, but always looking for best discounts.”

By Nayara Batschke