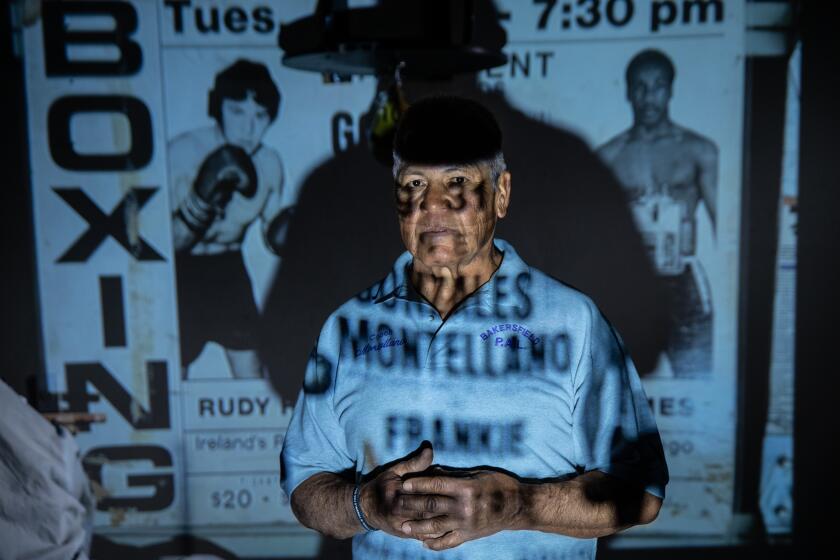

He was an unbeaten boxer bankrolled by Jay-Z. After an injury sent him into a coma, his new mission is helping fighters

Daniel Franco awaits a third surgery on Friday to replace the skull cap that was originally removed to reduce near-fatal brain swelling caused by his eighth-round knockout loss to Jose Haro in June.

Boxing has taken a heavy toll on many young and hungry fighters looking for fame and glory.

There are countless examples of inconsistent attention to the safety of the fighters. Rules pertaining to the health of boxers vary from state to state and country to country.

There is an implied acceptance of boxing’s deadly risk — part of the game, they say.

Daniel Franco understood those risks when he began boxing.

Now, after suffering a near fatal injury in the ring that ended his boxing career, Franco is looking to become an advocate for boxers who can learn from his experience inside and outside the ring.

The 25-year-old featherweight from Rancho Cucamonga was a young, unbeaten pro who had signed with Roc Nation Sports, a then-fledgling boxing promotion company bankrolled by rapper Jay-Z that also counted world champions Miguel Cotto and Andre Ward as clients.

Last week, as Jay-Z’s confessional album “4:44” was honored with eight Grammy nominations, including album of the year and record of the year, Franco sat at a four-chair dinner table inside his family’s humble condominium, wearing a glorified bicycle helmet to protect the section of his brain where a chunk of his skull is missing.

He spoke while gently stroking the stapled line along the left side of his head as he awaited a third surgery on Friday to replace the skull cap that originally was removed to reduce near-fatal brain swelling caused by his eighth-round knockout loss to Jose Haro on June 10 in Iowa.

The skull cap was taken off again following an infection that also nearly killed him.

It had been 172 days since a representative from Roc Nation had contacted him, he said.

“I feel … like I’ve been left in the dust,” Franco said. “They never valued me as a person. All I was was a product.”

Franco’s father, Al, said he was reduced to begging Roc Nation executives Michael Yormark and Dino Duva, asking whether the company — or Jay-Z or his wife, Beyoncé — could use one of their powerful social media platforms to promote Daniel’s GoFundMe campaign, which has raised more than $60,000 to help offset the family’s medical and travel costs, with nearly $200,000 in remaining bills.

No such assistance was granted, and the younger Franco recently noticed that Roc Nation Sports’ fighter stable had dwindled to a handful of fighters. Franco has been deleted from its website.

Asked what the company has done to help Franco, Yormark, said, “I have no comment.”

“It’s just a situation we, you know, we’re not happy about … and I’m not allowed to comment on. Our policy is we can’t comment on that subject,” Duva told The Times.

“Everybody cares about Daniel Franco and his medical and physical condition.”

That Franco is alive is remarkable.

He suffered his first pro defeat March 23 in what was expected to be a tuneup against light-punching Christopher Martin in Los Angeles.

Instead, Martin scored a third-round technical knockout.

“[Daniel] had been sick with the flu, out of the gym for three weeks, but [Roc Nation] wanted to push forward with the fight,” said Al Franco, who trained his son from age 8.

“My experience is, you pull out of fights, you get shelved. Promoters don’t like that. That’s why they don’t like trainers to be too close to fighters. They need a fighter to fight.

“After that fight, I was hot. I told those guys I saw this coming.”

Seven weeks after the loss, Franco agreed to a Roc Nation matchmaker’s suggestion to keep busy by fighting in Mexico, defeating a winless opponent in order to land the CBS Sports Network-televised main event in Iowa less than a month later.

At the face-off, Haro whispered to Franco, “I hate this,” the interaction being Franco’s lone memory of his final fight week.

Plans to win by controlling the fight’s tempo, pace and range were undermined in the first round by a Haro punch that dazed Franco.

In the sixth round, Haro scored a knockdown. Haro’s fateful knockdown punch to the head in the eighth was delivered in response to Franco’s missing a hook.

“It looked dramatic because [Daniel] was turning. He didn’t catch himself going down,” his father said.

“When we tried to get him on the stool, he couldn’t lift himself with his right leg. … Then he started complaining about a headache, and his speech started slurring. I knew we needed to get him to the hospital. In the ambulance, he started convulsing.”

A boxing veteran, Al Franco had witnessed others trapped in this spiral.

It’s why he frequently warned his fighters to remain in elite shape, reminding them there are about nine boxing deaths a year.

Now, peering into his son’s hospital room with emergency personnel swarming, his mind thought his son was next on that list.

“I thought he was going to die. … We were moved into the chapel — never a good thing — when the doctor came in to tell us Daniel had a brain bleed, and they were getting ready to go in,” Al Franco said.

“That’s kind of like … getting ready to put the nail in the coffin.”

While undergoing emergency brain surgery and a subsequent procedure, Daniel Franco was found to have suffered two skull fractures and a separate brain bleed that the surgeon said likely occurred in fights before the loss to Haro.

Al Franco said a doctor told him that if a scan or MRI had been used to inspect his son’s brain and skull before the Iowa fight, the bleed and cracks would’ve been found, sparing Daniel from more severe damage.

But he never received a post-fight scan after the California knockout.

One improvement from the Franco case could be state athletic commissions increasing their use of MRI and CT scans on fighters following knockdowns and knockouts.

In Nevada and California, a fighter is required to undergo skull or brain imaging only once every five years, unless a doctor orders a special exam following a fight.

One of Daniel Franco’s saving graces was that the apparent bleeding from the Haro bout was near the brain’s surface, quickening the life-saving treatment and helping to accelerate his recovery from a coma that lasted nearly two weeks.

There were fears the boxer would be paralyzed or left in a vegetative state.

“I thank God for my life every single day,” he said.

Franco speaks slowly and moves cautiously, but he recalls career events apart from Iowa and has strong opinions on a variety of subjects, including why younger super-featherweight champion Vasyl Lomachenko will defeat Roc Nation’s older, smaller super-bantamweight champion, Guillermo Rigondeaux, in Saturday’s bout in New York.

“As many times as I’ve seen this happen, he’s the only one sitting here — talking, walking, able to do all that he’s doing,” Al Franco said of his son.

Franco, who earned $6,000 in the loss to Haro, has posted on Instagram and Twitter a photo of him wearing the helmet and holding a sign reading, “I fought every time you asked. I never turned down an opponent. I sacrificed my life, my health, my future. I can’t even get a call?”

One physician has told Franco, who completed two years of community college, that he’ll “have a very hard time” trying to finish his education because of memory deficiencies caused by the injury.

So starting a foundation to help fighters who get injured is his new mission.

The cause aims to campaign for improved universal safety rules, health coverage and retirement plans. Some federal lawmakers are telling the Francos they’re interested in pressing an agenda that has long languished.

“I’m happy to speak for those boxers who got hurt and can’t talk. I want to make a change for this sport,” Franco said.

“Something hard never stopped me before. I want to help fighters avoid … all this.”

Twitter: @latimespugmire

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.