Great Read: The ghost of Prometheus: a long-gone tree and the artist who resurrected its memory

Somewhere in the high desert of eastern Nevada, a few turns off Route 50 — “the loneliest road in America” — a station wagon sat parked by the side of the highway. Before it lounged a young couple on red lawn chairs. A crudely painted wooden sign on the vehicle’s roof advertised: “Snow Globes $20.”

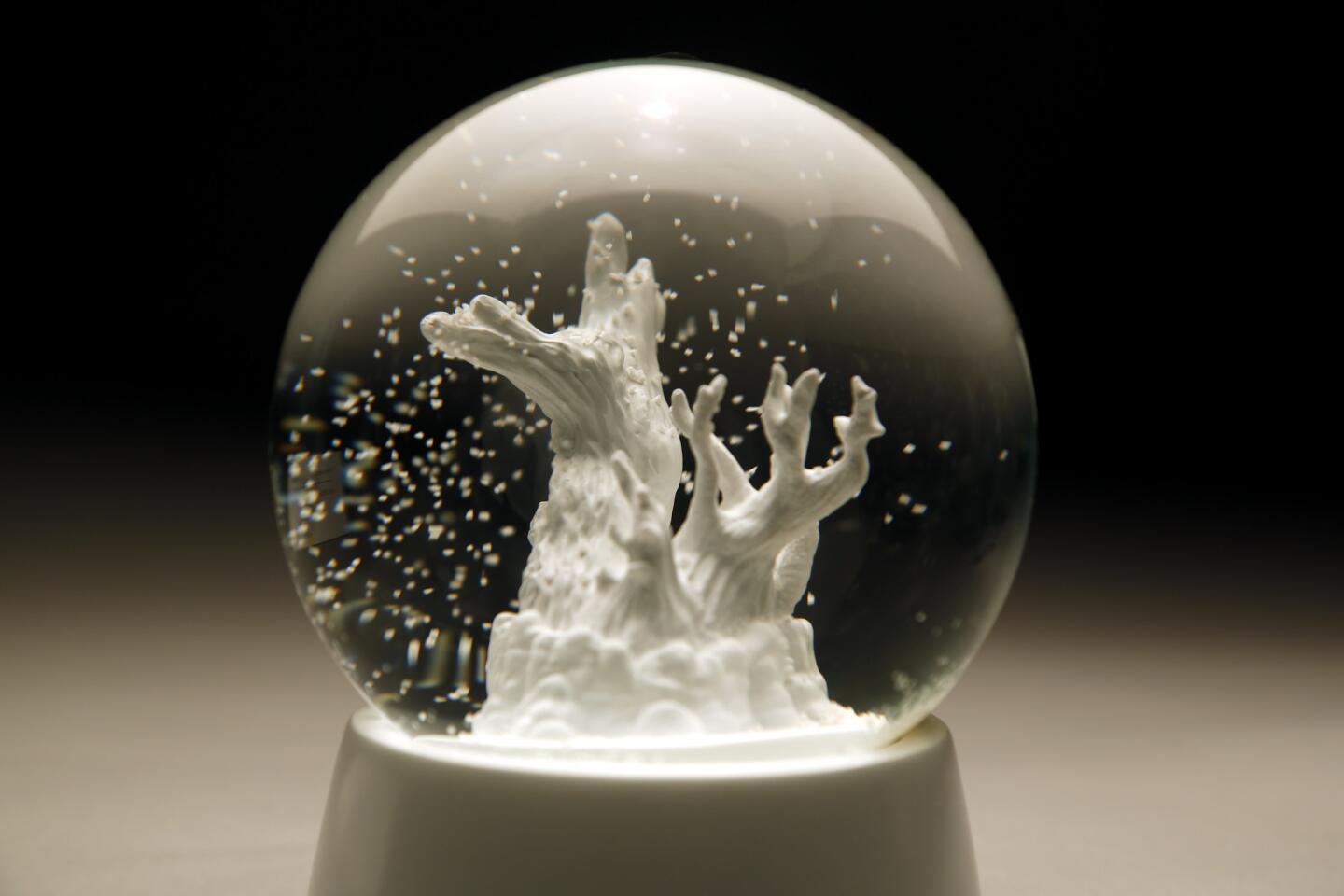

But this wasn’t standard-issue tourist bait. Each globe had been created by Los Angeles photographer and conceptual artist Jeff Weiss, and each contained an ethereal white rendering of a gnarled bristlecone pine that grew for roughly 5,000 years on the eastern fringes of the Great Basin.

The tree, called Prometheus, took root at the dawn of the Bronze Age, centuries before the ancient Egyptians began construction on the pyramids at Giza. It outlasted the rise and fall of the Roman Empire, European colonialism, the Mexican-American War and the creation of the atom bomb. But it didn’t survive the chainsaw that felled it on Aug. 7, 1964, at the request of a scientist who wanted to study the tree’s rings.

Weiss is obsessed with trees and the histories they hold; he has photographed them, created sculptures from them and is the kind of guy who will pull over on the side of a highway to examine unfamiliar specimens. (One afternoon, I ring him on his cellphone for a few follow-up questions. The connection is beyond terrible. “Where are you?” I shout. “Where else?” comes the staticky reply. “Looking at trees!” Weiss is standing in the middle of a sequoia forest.)

His obsession with Prometheus, however, has trumped all others.

Weiss has spent roughly four years re-creating the historic bristlecone: in drawings, digital renderings, a 3-D-printed sculpture that fits neatly in the palm of a hand. With the help of a Northridge artist, he even created a bonsai (which, in part, involves a sapling) that looks like Prometheus’ baby twin. There are also the snow globes — 500 of them. (“You have to order a minimum of 500,” he explains.)

Over the years, a plan took shape: a guerrilla memorial to mark the 50th anniversary of Prometheus’ death.

“The story of Prometheus, it has so many ingredients,” Weiss says. “There were people who said, ‘Don’t cut it.’ You have a Forest Service crewman who refuses to cut it. You have the various government groups in charge of the land — all these bureaucracies — who allow them to cut it. And you have these characters who may not have a lot of book knowledge, but they know stuff. It’s like a narrative straight out of the Old West.”

“The tree was the oldest living thing on Earth,” he adds, “and they cut it down.”

Prometheus was killed in the name of science. Weiss would resurrect it in the name of art.

::

Weiss has always loved spending time in the wilderness. But his fascination with Prometheus began not in the wild but in his Santa Monica apartment.

Just over four years ago, in the wake of a move and a bumpy divorce, he says he woke up one morning with a single thought in his head: “Go to the bristlecones.”

So he paid a two-day visit to the bristlecone grove in the White Mountains at Inyo National Forest in eastern California. He followed that trip with another. In the process, he stumbled upon the tale of Prometheus. Before he knew it, he was digging into scientific journals, interviewing scientists and making regular jaunts to eastern Nevada’s Wheeler Peak, the rugged quartzite mountain inside Great Basin National Park where the tree once stood.

Bristlecone pines are not conventionally beautiful trees. They aren’t slender, majestic towers like sequoias. And they don’t have the flamboyant crowns of the araucaria. They grow at dizzying altitudes (Prometheus lived at more than 10,700 feet above sea level) and inhabit supremely rocky terrain, surviving on trickles of rainwater, and adding just an inch to their girth every century.

Weiss admires their tenacity.

“Where they live,” Weiss says, “it’s like the worst place on Earth.”

Over centuries, as mountains move and the ground shifts, roots will become exposed and pieces of a bristlecone pine will die, even as others go on living.

“The trees,” muses Weiss, “are essentially dying their whole lives.”

Prometheus’ name was well chosen: In all those writhing branches, it’s hard not to see the Greek Titan for which it was named, recoiling in anguish as an eagle plucks his liver from his chest — Prometheus’ punishment for stealing fire for humankind.

The story of Prometheus, it has so many ingredients.

— Jeff Weiss, conceptual artist

::

There aren’t too many people in the art world like Weiss. Wiry, charismatic and voluble, he’s an artist who knows a lot of people yet chooses to occupy the fringes. A former art professor (he’s taught at UCLA and the Rochester Institute of Technology), he’s been exhibited in galleries and museums over a five-decade career. But these days, at the age of 72, he doesn’t have much interest in a system he feels has become relentlessly commercial.

“I don’t do galleries,” he says, “and I don’t ‘show.’”

His venue of choice is the Galley, the 80-year-old Santa Monica bar and grill known for its exuberant seafaring theme of fishnets and pufferfish lighting fixtures. It was at the Galley where Weiss and several friends he dubs his “accomplices” planned the remembrance ceremony for the “Prometheus Project.”

“This is my office,” Weiss says, sipping a margarita inside the confines of a bamboo-lined booth. “Every piece of the ceremony, every conversation, every problem, it was worked out right here.”

::

On a Wednesday in early August, an eclectic assemblage of artists, writers, photographers, graphic designers, students and friends traveled to eastern Nevada on Weiss’ instructions and checked into the Hotel Nevada & Gambling Hall in downtown Ely.

“At first, I was really hesitant. I was like, ‘I have to drive eight hours for this?’” recalls L.A. artist and photographer John Divola. “Jeff was pretty cagey about telling us what was going to happen.”

Waiting in every participant’s room was a snow globe and a sealed envelope with sightseeing and dining suggestions. There was also information about the next day’s remembrance, with instructions to tune their radios to local station KDSS-FM (92.7) on the drive to Wheeler Peak.

Weiss had persuaded Chuck Hutton, the host of KDSS’ “Mountain Morning Show” in Ely, to devote his program to Prometheus.

“Jeff just showed up here one day and asked if I would do a show about a tree,” Hutton recalls. “I didn’t know anything about the story. But Jeff was so passionate about it. I mean, I’m no tree hugger, but I’d say history has proven what an unfortunate mistake it was to take that living thing down.”

For an hour, Hutton played songs related to trees and memory: Faron Young’s “Live Fast, Love Hard, Die Young” and “Pine Tree” by June Carter and Johnny Cash. As Weiss’ guests wound their way through the high desert, past the snow globe stand, the mournful voices of Linda Ronstadt, Emmylou Harris and Dolly Parton pierced the static: “Those memories of you still haunt me / Every night when I lay down.”

The directions took everyone to an overlook inside Great Basin National Park, where they would participate in the remembrance ceremony: a pre-recorded memorial service that Weiss distributed on headphones as people arrived. (A public gathering without a permit would have violated park rules — the headsets allowed everyone to wander around as they listened.) This was followed by a symbolic watering of the bristlecone sapling, using water from a nearby stream.

“Being out there, in that place, it was an overwhelming experience,” says Lee Thompson, an L.A.-based photographer who served as an accomplice on the project. “And it’s mixed in with this work of art that is not like the typical work of art you’d expect. Being out there was a major part of it. And I don’t think that was unintentional on Jeff’s part.”

Divola concurs. “The whole piece — it’s not quite performance, it’s not quite sculpture, it’s not quite literature, it’s not quite any of those things,” he says. “But it’s certainly poetic. I don’t think I’ve ever been involved in anything quite like it.”

“It’s not quite performance, it’s not quite sculpture, it’s not quite literature, it’s not quite any of those things. But it’s certainly poetic.”

— John Divola, artist

::

It’s not over. Weiss is sorting through mountains of video and photography related to the project. He has the 3-D-printed model, several hundred snow globes and the sapling (which is still growing millimeter by millimeter at Kimura Bonsai Nursery in Northridge). His intention is to stage a Prometheus-related event somewhere in Los Angeles this year.

Like the remembrance at the Great Basin, it will likely be a guerrilla act. And like the remembrance, it is being plotted over margaritas at the Galley.

“There will be a Part 2 of some kind,” Weiss says. “But I’m still figuring out exactly what form it will take.”

Whatever it is, it likely won’t reside in any commercial gallery or pristine museum white box. “A bristlecone,” he says, “cannot survive indoors.”

For now, though, he’s satisfied knowing that he has created a wave of fresh stories about Prometheus, even if those memories can’t replace what was lost.

“I didn’t make the tree,” Weiss says. “Less than 50 people ever saw the tree. I made the memory of the tree. There’s no way to make the tree. It’s gone.”

Twitter: @cmonstah

ALSO

Follow-up: More tales of the Prometheus tree and how it died

Ancient bristlecone pine forests are being overwhelmed by climate change

How artist Camilo Ontiveros acquired the belongings of a DACA deportee and what he did with them

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.